Diagnosis

Testing and diagnosis

Screening and testing of patients at-risk of non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease (NTM-PD) are the cornerstones of effective diagnosis and treatment initiation

Effective diagnosis of NTM-PD is essential to drive prompt and successful treatment, particularly given that the chance of success is best with the first round of therapy.1,2

NTM is often misdiagnosed, and symptoms may mimic those associated with underlying chronic lung conditions.3,4 Delays in diagnosis of NTM-PD may mean that patients are subject to lung damage in addition to any caused by their original lung condition.5

Patients with a predisposition towards NTM-PD who present with worsening lung function should raise an index of suspicion for further investigation.6

Studies demonstrate a range of patients are at greater risk of having NTM, these include:

- Patients who have a marfanoid body habitus, ‘the so-called Lady Windermere phenotype’, (taller than average, low body mass index (BMI) <18 kg/m2, presence of thoracic skeletal abnormalities) are at a higher risk of having NTM-PD6,7

- Underlying lung conditions including bronchiectasis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) especially if treated with inhaled corticosteroids and asthma6–9

- Patients with underlying genetic predisposition – e.g. alpha -1 antitrypsin deficiency10,11

- Immunosuppressed or immunocompromised patients including those with rheumatoid arthritis, treated with steroids or transplant recipients6,12

- Patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)6

In these patients, with symptoms or worsening disease, rule out NTM-PD!

When NTM is suspected it should be diagnosed using:2

- Symptomology – lung function or systemic symptoms

- Chest CT scans

- Microbiological tests on sputum or bronchial lavage

Clinical symptoms that are compatible with NTM infection include:13

![]()

Chest CT scans identify areas of cavitation and should be used in preference to chest X-rays, which alone are insufficient to secure a diagnosis of NTM-PD. CT scans also identify areas of mucous that appear as characteristic ‘tree in bud’ opacity.3 Radiological features that are consistent with NTM infection include:3

- Reticulonodular infiltrates

- Multiple nodules

- Multifocal bronchiectasis

- Nodules and bronchiectasis occurring in the same lobe, often the right middle lobe and lingula

- Cavities

- Alveolar infiltrates

Repeated sputum samples from patients, obtained spontaneously or from bronchial lavage or wash should be evaluated microbiologically for the presence of NTM. In the first instance sputum examined microscopically can indicate if acid-fast bacilli (AFB) are present, a process that is relatively quick, and then sputum should be subjected to bacterial culture that can take several weeks.14,15 Once cultured further analysis to speciate infection should be undertaken.16 Alternatively, transbronchial or lung biopsy with mycobacterial histology (e.g. granulomatous inflammation or AFB) and positive sputum culture would be indicative of NTM-PD as would repeated bronchial washings that are culture positive for NTM.2

Typically, two or more consecutive sputum cultures of the same species would indicate that disease is active and treatment warranted and this is particularly true for MAC-PD, M. abscessus or M. xenopi. However, for species such as M. kansasii a single positive culture may be enough evidence to start therapy.2

Once NTM is identified and speciated and pulmonary disease diagnosed, treatment should follow that outlined in guidelines.2,17

Featured content

Video

Duration: 5 mins

In this video European experts provide their insights into the 2020 ATS/ERS/ESCMID/IDSA guidelines on NTM-PD, with a focus on MAC-PD.

Article

Read time: 8 mins

Non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease (NTM-PD) can be life threatening and is increasing in prevalence. International guidelines updated in 2020 provide management recommendations for the four most commonly occurring NTM pathogenic species.

Video

Duration: 7 mins

Microbiology is pivotal to the diagnosis and treatment of MAC-PD. In this video experts share their thoughts on the role of microbiology in diagnosis, in determining effective treatment strategies and in ongoing monitoring towards culture conversion.

Find out more about NTM-PD

Explore which patients to treat, and when a decision to treat has been made, how to do this in line with current guideline recommendations

References:

- Griffith DE et al. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2012;25:218–27.

- Daley CL et al. Eur Respir J 2020;56:2000535.

- Griffith DE et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;175:367–416.

- Maiga M et al. PLoS One 2012;7:e36902.

- Lee MR et al. PLoS One 2013;8:e58214.

- Prevots DR et al. Clin Chest Med 2015;36:13–34.

- Dirac MA et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;186:684–91.

- Andrejak C et al. Thorax 2013;68:256–62.

- Hojo M et al. Respirology 2012;17:185–90.

- Szymanski EP et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015;192:618–28.

- Wu UI, Holland SM. Lancet Infect Dis 2015;15:968–80.

- Winthrop KL et al. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:37–42.

- Rare disease database. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/nontuberculous-mycobacterial-lung-disease/ [Accessed February 2021].

- Lab Tests Online. https://labtestsonline.org/conditions/nontuberculous-mycobacteria-infections [Accessed June 2020].

- National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/7123/mycobacterium-aviumcomplex-infections#ref_15023 [Accessed June 2020].

- Koirala J. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/222664-print [Accessed February 2021].

- Haworth C et al. Thorax 2017;72(Suppl 2):ii1–ii64.

An overview of the 2020 ATS/ERS/ESCMID/IDSA clinical practice guideline for the treatment of non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease

Non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease (NTM-PD) can be life threatening and is increasing in prevalence. International guidelines updated in 2020 provide management recommendations for the four most commonly occurring NTM pathogenic species.

Non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) are ubiquitous in the environment.1 The clinical presentation of NTM infection is most often pulmonary disease (PD), and rates are highest in elderly people, and in those with underlying structural airway disease, cancer or immunodeficiencies.1,2 Diagnosis and treatment of NTM-PD can be difficult2 and its prevalence is growing.1 Published in 2020, ATS/ERS/ESCMID/IDSA jointly sponsored the development of a guideline updating management recommendations for NTM-PD in adults.1 Recommendations for diagnosis and treatment of the most common pathogenic NTM species and the perspectives of international thought leaders on guideline recommendations are summarized here. The appearance of new guidelines in 2020 was widely welcomed by NTM experts.

“These guidelines represent an important achievement after 13 years with a rigorous, great methodology, starting from 22 PICO [Population, Intervention, Comparator and Outcome] questions addressed in these guidelines resulting in 31 recommendations touching the management of patients with NTM, including Mycobacterium avium complex, M. kansasii, M. xenopi or M. abscessus. The task force was composed of representatives from four different international societies, two from the US and two from Europe plus patient representatives, so a very important document in 2020”. Stefano Aliberti, University of Milan, Italy

Diagnosis

The ability of NTM to cause disease differs between species, with M. xenopi, M. kansassi, M. abscessus and Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) of which M. avium and M. intracellulare are the most common species being responsible for most NTM-PD.1 It is clear from experts that awareness of NTM remains relatively low so understanding which patients might be at risk of NTM-PD can be suboptimal.

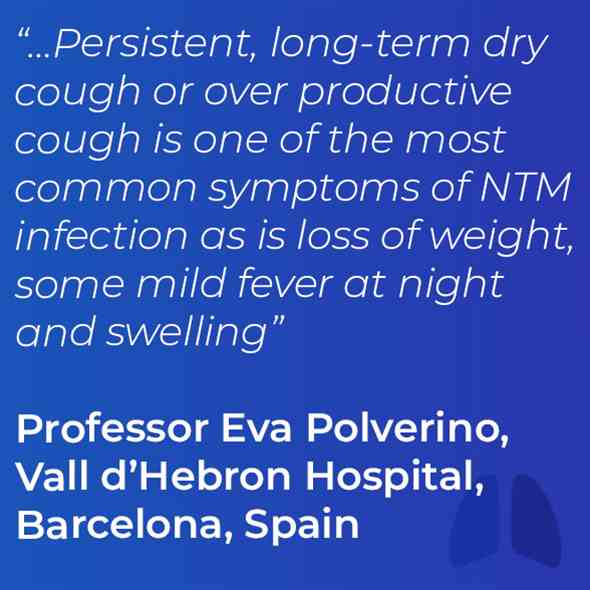

“Women are usually more affected than men and of course a number of patients with particular conditions like cystic fibrosis [and], or some kind of immunosuppression”. She went on to say that “It is difficult for many people to understand what patients should be tested for NTM, and when and for these you should be aware about compatible signs and symptoms. For example, persistent, long-term dry cough or over-productive cough is one of the most common symptoms, as is loss of weight, some mild fever at night and sweating”. Eva Polverino, Vall d’Hebron Hospital, Spain

Diagnosis relies on clinical, radiographical and microbiological data — laboratory identification to a species or subspecies level is key both in diagnosis and treatment decisions.1

The four most common pathogenic species are Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC), M. kansasii, M. xenopi and M. abscessus.1,3

- Clinical signs of NTM-PD include cough, sputum production, haemoptysis, dyspnoea chest pain, malaise, weight loss and night sweats.3

- Radiological signs are nodular or cavitary opacities on chest radiograph, or bronchiectasis with multiple small nodules and tree-in-bud pattern on high-resolution computed tomography scan.1

- Microbiological confirmation (one of the following) is obtained from:1

- positive culture results (same NTM species) from at least two sputum samples

- positive culture results from at least one bronchial wash or lavage

- transbronchial or other lung biopsy with mycobacterial histological features (granulomatous inflammation or acid-fast bacilli) and, either

- positive culture for NTM, or

- one or more sputum or bronchial washings culture positive for NTM.

Treatment

The recent guidelines recommend treatment initiation rather than watchful waiting on diagnosis of NTM-PD, but drug therapy should follow a careful discussion of risk–benefit with the patient.1 Treatment varies according to the species, extent of disease, drug susceptibility results and the patient’s underlying comorbidities.1 Regimens often require administration of multiple agents associated with clinically significant adverse events for a prolonged period, outcomes are often suboptimal and reinfection common. Expert consultation is often helpful.1

Guideline recommendations are made in several scenarios for patients infected with MAC, M. kansasii, M. xenopi or M. abscessus.1 However, before treatment is initiated understanding drug susceptibility for those drugs being considered for treatment is important.1

“The new guidelines do provide recommendations on drug susceptibility testing and they state that drug susceptibility testing should be performed before initiating treatment for MAC pulmonary disease for example. Importantly they state so for 2 drugs or groups of drugs, for macrolides and for amikacin. Testing amikacin susceptibility is very important because amikacin, as an IV drug, may be required in the initial phase of treatment in patients with very severe disease and in patients with refractory disease”. Jakko van Ingen, Radboud UMC, the Netherlands

Similarly, for M. abscessus susceptibility testing for macrolides and amikacin is also recommended, whilst for M. kansasii the guideline recommends susceptibility testing for rifampicin.1 For M. xenopi the guideline indicates there is insufficient evidence to recommend any specific susceptibility testing.1

MAC1

Macrolide-susceptible MAC-PD1

- A three-drug regimen including a macrolide is suggested in preference to a two-drug regimen that includes a macrolide and is recommended over a three-drug regimen with no macrolide.

- Macrolide susceptibility consistently predicts treatment success; regimens with no macrolide are associated with reduced rates of negative sputum-culture conversion, and with higher mortality.

- Three-drug regimens are recommended owing to a lack of evidence for the relative risk of macrolide-resistant MAC developing with two-drug versus three-drug regimens.

- In patients with non-cavitary nodular/bronchiectatic disease, administration of a macrolide-based regimen three times per week is preferable to daily administration.

- Intermittent and daily therapies have similar sputum conversion rates, but intermittent treatment is better tolerated and not known to be associated with development of macrolide resistance.

- In patients whose therapy has failed after at least 6 months of guideline-recommended oral guideline-based treatment, once-daily Amikacin Liposome Inhalation Suspension (ALIS) should be added to the treatment regimen.

- After culture conversion, patients should continue treatment for at least 12 months.

- This is based on the 2007 guideline recommendation (12 months of negative sputum cultures), and a lack of data on optimal duration of therapy.3

Newly diagnosed macrolide-susceptible MAC-PD1

- It is suggested that azithromycin-based, rather than clarithromycin-based, regimens are used and that initial treatment should not include inhaled amikacin (parenteral formulation) or ALIS.

- Clarithromycin and azithromycin have equal efficacy, but azithromycin is better tolerated, with fewer drug interactions, lower pill burden and is taken once daily.

Cavitary or advanced/severe bronchiectatic or macrolide-susceptible MAC-PD1

- A macrolide-based regimen administered daily rather than three times per week is suggested.

- No randomised trials have evaluated the the risk of macrolide resistance associated with intermittent versus daily regimens, so a daily regimen is preferred.

Cavitary or advanced/severe bronchiectatic or macrolide-resistant MAC-PD1

- Parenteral amikacin or streptomycin is suggested as part of initial treatment.

- Parenteral aminoglycoside is among very few options for ‘intensifying’ standard oral therapy in MAC. Administration of aminoglycoside for at least 2–3 months balances associated risks and benefits.

M. kansasii1

Rifampicin-susceptible M. kansasii-PD1

- A regimen of rifampicin, ethambutol and either isoniazid or a macrolide is suggested instead of a fluoroquinolone. It is also suggested that neither parenteral amikacin nor streptomycin be used routinely. Patients should be treated for at least 12 months.

- Isoniazid is widely used with rifampicin and ethambutol, with good outcomes. Two studies substituting isoniazid with clarithromycin also showed good treatment outcomes. There is less experience for substitution with a fluoroquinolone, but this can be used in cases of antibiotic intolerance or rifampicin resistance.

- Apart from in severe disease or where rifampicin-based regimens cannot be used, the risk of adverse reactions counts against parenteral amikacin or streptomycin.

- Daily administration is suggested for all patients receiving rifampicin, ethambutol and either isoniazid or a macrolide.

- Patients with non-cavitary nodular/bronchiectatic disease receiving the macrolide-containing regimen can also be treated three times weekly.

M. xenopi1

All patients1

- A daily treatment regimen of at least three drugs is suggested: rifampicin, ethambutol and either a macrolide and/or a fluoroquinolone (e.g. moxifloxacin). It is suggested that treatment continues for at least 12 months after culture conversion.

- In cavitary or advanced/severe bronchiectatic disease, adding parenteral amikacin to the treatment regimen and obtaining expert consultation are suggested.

- On current evidence, patients should be treated aggressively given the high mortality associated with xenopi-PD.

M. abscessus1

All patients1

- A regimen of at least three drugs is suggested (selection guided by in vitro susceptibility)

- The disease can be life threatening. Treatment regimens should be designed with expert guidance in particular with respect to treatment duration.

Strains without inducible or mutational resistance1

- A macrolide-containing multidrug treatment regimen is recommended.

- In vitro macrolide-susceptibility testing is important.

Strains with inducible or mutational macrolide resistance1

- It is suggested that a macrolide can be included for its immunomodulatory properties but is not considered part of the antibiotic regimen.

“In addition to antibiotic therapy close monitoring of the patient and patient education is very important. One of the major mistakes done in the management of patients with Mycobacterium avium pulmonary disease or any other NTM pulmonary disease, is the lack of proper monitoring, for example monthly sputum collection for microscopy culture. Also the weight of a patient and symptoms, systems recording like sputum production or fatigue recording are important as part of the monitoring of a patient during the treatment”. Christoph Lange, Research Center Borstel, Germany

The guidelines published in 2020 are very welcome in this often overlooked area of respiratory medicine. However, it is clear that treatment for patients with NTM-PD remains arduous and lengthy with multiple drug regimens that are required for 12 months or more post-culture conversion.

Abbreviations

ALIS, Amikacin Liposomal Inhalation Solution; ATS, American Thoracic Society; ERS, European Respiratory Society; ESCMID, European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases; IDSA, Infectious Diseases Society of America; MAC, Mycobacterium avium complex; NTM, Non-tuberculous mycobacteria; NTM-PD, Non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease; PD, pulmonary disease.

References:

- Daley CL, et al. Eur Respir J 2020;56(1):2000535.

- Ratnatunga CN, et al. Front Immunol 2020;11:303.

- Griffith DE, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;175:367–416.

![]() Medical writing and editorial support was provided by Highfield, Oxford, UK. This support was sponsored by Insmed.

Medical writing and editorial support was provided by Highfield, Oxford, UK. This support was sponsored by Insmed.

Thank you for registering your interest

Sorry, an error has occurred: